Having covered the Western Campaign, the Battle of Britain, and the first phase of RAF Bomber Command‘s assault on the Third Reich, it’s time to start the United States’ portion of the Strategic Bombing Campaign. Again, in the interest of brevity, I’m going to do a little background then make liberal use of the fast forward button so we can actually discuss punches getting thrown.

In World War II, just as in World War I, the United States had a little bit to get the lay of the land before joining hostilities. Unlike Great Britain, the United States did not have an independent air force in the years leading up to World War II. Indeed, the United States’ main air prophet, Billy Mitchell, got so uppity about airpower the Army court-martialed him. Still, even without someone going full Trenchard, the United States Army Air Corps was able to hoodwink Congress into buying the B-17 and B-24 ostensibly to attack ships at sea from high altitude. Neither bomber performed this task very well throughout World War II, but at least having the designs on hand meant strategic bombing was on the table.

Note I said possible, not prudent. A prudent person looking at the Battle of Britain and ongoing events over Western Europe might have said, “Mmm, maybe we should figure out this fighter escort thing.” But remember, this is the same Army organization that didn’t listen to Claire Chennault about the Zero (we’ll get to that for those of you who have no idea what I’m talking about) and also didn’t relieve the guy who got his bombers all caught on the ground nine hours after Pearl Harbor. In short, if you had to list antonyms for dynamic, forward thinking organization that reacted quickly to military realities, the US Army Air Force circa January 1943 probably cracks the World War II Top Ten. (Number one is the Imperial Japanese Navy’s General Staff, for those wondering.) The USAAF was convinced that the reason the British and Axis had been smacking each others’ bombers around was that no one in Europe knew how to properly mount defensive armament or organize a bombing campaign. Good ol’ American ingenuity, as well as an eye wateringly massive industrial bases was expected to put the Old World right pretty quickly.

This fantasy was reinforced by the initial raids into Europe. By the time the Casablanca Conference rolled around, the Americans were truly ready to test their luck. Slight problem: Most of the RAF thought their plan was crazy. As in, I imagine the conversation between 8th Air Force Commander Ira Eaker and the British generals going something like this:

“So old boy, when shall we begin night training for your chaps?”

“Excuse me?”

“Your heavy bombers? I mean, once this North Africa sideshow is over, certainly you’ll have dozens if not scores of bombers available to join ol’ Butch’s boys at night?”

“Um, did you read the doctrine I sent you? We’re going in daylight.”

*polite chuckle followed by look of sheer horror British Air Staff realizes Eaker’s serious*

Most of the RAF and Royal Navy, being unable to wrest bombers away from Sir Arthur Harris, thought the American Flying Fortresses and Liberators would make awesome anti-submarine aircraft. Or, failing that, the Americans would make great additions to tactical/operational raids into France. Harris, of course, figured the B-17s would make great additions to the night bombing campaign once they lost their armor and excessive machine guns. In any case, everyone but the USAAF thought going to bomb Germany in daylight sounded truly idiotic.

So great was British apprehension that Winston Churchill left for the Casablanca Conference planning to get Franklin Roosevelt to overrule his crazy generals. Unfortunately, Ira Eaker preached like a zealot and sold like a snake oil salesman. American bombers had the Norden bombsight. They were also hardier than their RAF counterparts and more heavily armed. Finally, appealing to Churchill’s sense of vengeance, Eaker dropped the money quote:

“If the RAF continues night bombing and we bomb by day, we shall bomb them round the clock and the devil shall get no rest.”

Churchill, always happy to inflict pain on Nazi Germany, thought that sounded splendid. Franklin Roosevelt did as well. Between them, they ensured the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued the necessary orders to make strategic bombing a priority task.

Was the USAAF that crazy, or just overly optimistic? Well, at the time, the Norden was a marvel of technology when first fielded. Put into production in the 1930s, it allegedly gave American heavy bombers an accuracy far superior to the Axis or Allied contemporary sights. Although apocryphal tales of it allowing bombardiers to drop their loads “into a pickle barrel” during testing were widely circulated, in actuality circular errors of probability (CEPs) of 500 feet were not uncommon during testing. Given the average size of 1940s manufacturing plants, American air zealots were certain that enough B-17s would start blowing German industry back to Renaissance.

Defensively, the bomber barons expected “Ma Deuce” to see them through. For those who are unfamiliar with American military slang, “Ma Deuce” is the nickname for, quite simply, possibly the best American machine gun ever fielded. I present the Browning M-2 .50 caliber machine gun:

I could go on for days about the M2. It’s been killing the Republic’s enemies since right after World War I, and it has made no distinction between Nazis, Kamikazes, Chinese Communists, Vietcong, terrorists…wait, sorry, got lost in the moment there. The reason for it longevity is that the M2 is not necessarily the best in any particular category, but is the epitome of “good enough to see you through.” For aerial warfare purposes, this weapon was basically the standard machine gun used by US forces throughout World War 2. Fighters mounted them in groups of 4, 6, or 8…but the B-17 / B-24 carried 10-16 (yes, 16!) depending on the model.

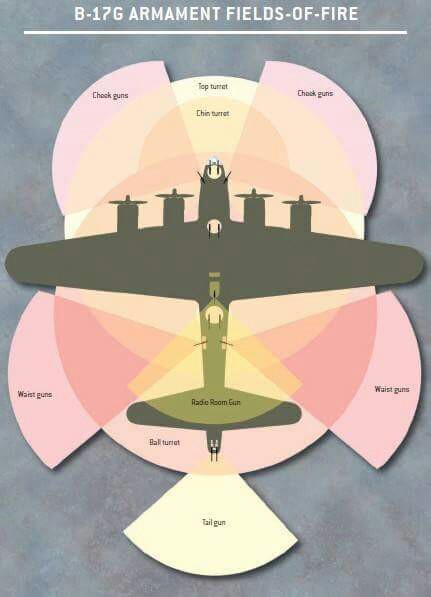

Thus, it wasn’t the excellence of the individual machine guns and expected accuracy of the young kids wielding them that gave the USAAF confidence. No it was the fact that when you start talking about an entire squadron full of machine guns, things get interesting. First, allow me to present 2 diagrams of what a B-17’s firing sectors looked like:

Now, mind you, this is after chin turrets were added, but you get the idea that attacking a single B-17 was like deciding to play “.50-caliber lotto.” I mean, a few months after Casablanca, a solo B-17 fought off hordes of (albeit lighter) Japanese fighters while inflicting massive casualties. So, given the experiences over France and the war to date, it was not utterly insane to think the B-17 was a tough out.

As if each B-17 was not bad enough, then Colonel Curtis Lemay helped refine a formation that made them even deadlier: the combat box.

Imagine, if you will, it’s January 1943, and you’re a German ace. You’re a bad mofo with over 100 kills to your credit. Spitfires have blazed under your guns. You’ve dusted Lightnings in North Africa. The Russians speak your names in hushed whispers while hoping their bladders don’t betray them. You’re familiar with American twin-engine bombers because, hey, Lend Lease (“Neutral my schnitzel!”). So you get scrambled to go attack some bogeys heading to northern Germany and you see that rolling ball of pain coming at you. What do you do?

Well, initially you open fire at too far a range because the B-17’s size makes it look closer than it is, get the living shit shot out of you and your wingman, and generally come back to base needing a change of underwear. From any one direction, you’re looking at ~40 machine guns wielded by angry American draftees. A large percentage of these men are used to hunting birds for literal survival, and 100% of them are pissed off they’re over Germany. Collectively they’re not super accurate, and fire discipline sometimes gets out of hand, but quantity of fire has a quality all of its own. By about the tenth penetration of German airspace, Adolf Galland is apoplectic in telling the boys at R&D they better figure something out.

Germans being Germans–they figured something out. The first steps were simple things like “Hey, maybe we should put more armor on our interceptors? It’s not like we gotta worry about escort fighters, so who cares if they’re clumsier?!” The second was to increase the number of cannons carried by both the 109 and the 190. While the closure rate was such that there wasn’t a huge range advantage of cannons over M2s (and most folks couldn’t hit at long range anyway) and the gun pods made the fighters clumsy as hell, the more damage done in a pass the better. Finally, the Luftwaffe resorted to improvised rockets. As in, “Hey, Wehrmacht buddies! We know you’re neck deep in Russians right now, but could we borrow some of your ordnance so your uncle doesn’t get whacked at the factory? Thanks! We promise we’re making our own rockets!”

As the saying goes, by July-1943 “shit got real” on both sides. For the Germans, both experienced and neophyte pilots alike were getting attrited by Farmboy Neds rolling a “100” on their to hit roll. Escort P-47s, despite their limited range, were still managing to take their own toll. Worse, even when they weren’t killing pilots, American bomber formations were causing so much damage to fighters that the Jagdwaffe‘s operational readiness rate was drifting into the 50-60% range. When squadrons were starting a week with 16 available birds then ending it with only 5 despite receiving 7 replacements, it didn’t take a rocket scientist to realize something had to give.

Oh, and by the, remember how we talked about the British? Yeah, Sir Arthur Harris’ boys were more than keeping up their end of the “bomb them around the clock.” In addition to their usual mayhem, they burned a huge hunk of Hamburg to the ground in July 1943. This was a rather significant emotional event for the Germans, it being the first manmade firestorm and all.

This incident gave the entire Nazi leadership the vapors for about two weeks. Given the American bombers just tooling around in daylight and the British playing “Come On Baby Light My Fire” in the key of Lancaster, Galland was forced to strip fighters from the Eastern and Mediterranean fronts. To say this was the last thing the German ground forces needed would be an understatement, but Adolf Hitler and Hermann Goering, et. al. gave him no choice. Having come to to power spouting the (erroneous) “stab in the back“-theory, the Nazis wanted to give the German civilian populace no reason to give up. (“Um, you are aware there’s this Soviet bird of prey called the Sturmovik, right?”–German Panzer crewmen from August 1943 on.)

Sounds grim, doesn’t it? Well, the only people having it worse than the German Jagdflieger were American bomber crews. The German fighters were causing damage and getting kills. Complementing these slashing attacks, German flak was doing things like this:

Except, in most cases, the crews were not making it back to take commemorative pictures. All too often, the last time someone would see a flak damaged B-17 was in its death spiral, with friends and comrades trying to see how many, if any, chutes got out.

The German defenses were so strong that by August 1943 it was statistically impossible for an Eighth Air Force bomber crew to survive their 26 mission tour. As in, “The reason everyone remembers the Memphis Belle is the logic on why lotteries announce their jackpot winners: the powers that be want to maintain false hope.” From the American perspective, it seemed that the Germans improved their ordnance, their flak, and their skill at head on passes every mission. Each B-17 and B-24 that fell took 10-12 men with it. That started to add up in the KIA/POW/MIA columns in an alarming rate, affecting morale. Exacerbating this, like their German counterparts in the Battle of Britain, damaged bombers also brought back wounded crew members with them. Scenes akin to these these started becoming all too common across eastern England:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9LZP5R109yo&w=560&h=315]

Two battles pretty much put the exclamation mark on the “Hey stupid, stop that!”-phase of the USAAF’s offensive: Schweinfurt-Regensburg and the Army’s return trip to the Schweinfurt ball bearing plants. Long story short, the USAAF’s targeting folks decided that ball bearings were the critical material for the Nazi war machine, and Schweinfurt was believed to be the “one shot, one kill” node of air power fantasies. So, the first time, the USAAF tried to be cute and launch a double penetration to split the German defenses on August 17, 1943–the one year anniversary of their first raid with B-17s against occupied France. The double mission went…poorly. Over 60 bombers were lost, and the 8th Air Force took almost a month to fully recover. Even worse, while the aircraft factory at Regensburg was devastated, the ball bearing plants at Schweinfurt were hardly touched.

For those of you who have seen Rocky IV, this point in the air campaign is analagous to where Apollo Creed’s manager was screaming “Throw the towel! Throw the damn towel!” The purpose of strategic bombing, the logic went, was to avoid bloodletting in large doses, not reenact the Battle of the Somme in the sky. Speaking of the British, the RAF was watching all this in sheer terror openly stating “We told you bloody colonials what would happen but noooooo.” Seriously, go read Harris’ and several other senior British leaders memoirs. Claire Chennault and other fighter generals, having tried for years to get the USAAF to focus on long-range fighter development, soundly cursed Hap Arnold’s mule-headed behavior and Ira Eaker’s poor choice of escort tactics. George C. Marshall wondered if the Allies would actually gain air superiority in order to allow a cross-Channel invasion.

So, in the face of all this, Ira Eaker doubled down on stupid. There are accounts of men actually screaming profanities at their leaders when the briefing map was unveiled on 14 October 1943. Like Union soldiers pinning their names and hometowns on their back at the Battle of Petersburg, men wrote last letters home, boxed up their stuff, and undertook all manner of tasks that would make their friends’ lives easier when they did not return. Everyone knew that the German defenses had only gotten stronger in the intervening two months since the last trip, with the attack almost certainly suicide. As the escorting fighters turned away at the limits of their range, the pilots could see a veritable horde of German fighters lurking in the distance just waiting for the B-17s to come closer.

As military debacles go, Black Thursday was just short of the Charge of the Light Brigade. Two hundred-ninety-one B-17s were launched. Of these, roughly 10-15 aborted due to malfunctions, leaving 281. The German fighter attacks were so intense that numerous B-17s ran out of ammo before even reaching Schweinfurt. The German flak concentration at Schweinfurt was considered the most dangerous to that date in the war. Indeed, the concentration was so dense that veterans of future raids to Berlin would still swear Black Thursday was the heaviest anti-aircraft fire they ever saw. Forced to fly straight and level from their initial point to bomb release (as they did in all missions), the B-17s were sitting ducks. Turning for home, they found themselves confronted with the same German fighters they had faced that morning after the latter had refueled and rearmed.

By the end of the day, the butcher’s bill was astounding. Sixty bombers were destroyed outright. Depending on the source, roughly 20 more were written off. Another 100 were damaged. These losses were not distributed evenly, and entire bomb groups basically ceased to exist. Personnel wise, casualties were horrific. Due to the extreme range of the mission, almost every critically injured bomber crewman died of wounds before reaching England. Almost 600 men were KIA, POWs, or MIA.

Starkly, by nightfall on 14 October, the Eighth Air Force had been rendered combat ineffective. Even worse, it had been for little appreciable gain. Having been sufficiently frightened by the first raid, the German war industry had built up reserve stocks of ball bearings, plus acquired more from neutral countries like Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Portugal. In the end, German production in general and of ball bearings in particular did not even slow despite many of the works being severely damaged.

The USAAF tried to put a happy face on things, but no one above Ira Eaker was amused. Given the scale of the disaster, something had to give. General Eaker was “fired laterally,” being sent to the Mediterranean Theater to take over a then nonexistent Fifteenth Air Force. Lieutenant General Jimmy Doolittle, leader of the famous Tokyo Raid, was promoted into Eaker’s place. Severely chastened, the Eighth Air Force began to examine how they could resume the offensive once 1944 came. Help, ironically due to a British request for a new fighter aircraft, was on the way:

Note: Usually I do a reading list at the end of each of these. Seeing as how I have an entire Strategic Bombing bibliography somewhere on my computer, this will likely get printed as an entirely separate blog entry.

[…] Yankee Doodle Went t… on Sergeant Pepper Bombs Mr. Adol… […]